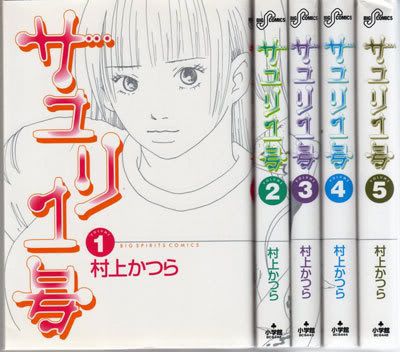

Sayuri 1-go 1-5 and Cue 1-3 - Katsura Murakami

Two series from the early-middle parts of this decade that ran in Big Comic Spirits. Murakami is one of those female artists in seinen magazines, similar to Fuyumi Soryo (Eternal Sabbath, Mars), with that recognizable art style: not weighed down with enough obsessive detail to be done by a man, yet not gauzy and abstract enough to be shojo. Sayuri 1-go was her serialized debut, and it originally struck a chord with me. As anyone who has had to suffer through my blubbering rants about Boys on the Run can attest, I am a total sucker for extremely painful and unsentimental romance stories about losers and fatally flawed characters. Sayuri is a story set in a college club (or "circle" as they're called in Japanese). A young man and woman are the leaders and organizers of the circle and have known each other since childhood. Naturally, the boy (Naoya) is much too close to the girl (Tomoko) to see her as a romantic interest, but she does love him. So far pretty unremarkable, right? The story begins when an attractive new underclassman, Yuki, joins the circle and immediately grabs the attention of all the male members. As a matter of fact, her face is identical to "Sayuri," the imaginary girl that Naoya has used for masturbation material ever since he was old enough to jerk off. Now we're getting somewhere! As if Naoya's instant infatuation with her and awkward, unintentional references to her as "Sayuri" weren't bad enough, Yuki is a manipulative, borderline psychopath who has joined and quit multiple circles after seducing members for the pleasure of seeing good personal relationships go sour, all stemming back to a traumatic childhood of constant moving every year and the inability to ever have a meaningful friendship. The drama is generally pretty taut and it moves along quickly and entertainingly. As a story about young adults, it straddles a taut line between developing maturity and the darker, animal instincts of the human race--a topic too advanced for adolescent romantic-comedies. Time and time again, Yuki shows how the capacity for self-delusion and the dangerous allure of "being treated special by someone special" can be used to unhinge men's ties to their friends and lovers. At some point, the story tips a scale of realism when, after the astonishing breadth of Yuki's almost inhuman machinations are brought to light, the characters choose not to simply shun her and lick their wounds, but to embrace her and "cure" her of these devastating personality flaws. The last two volumes are dedicated to this character rehabilitation, but in a shocking finale, Naoya learns one too many unpleasant facts about her, and abandons her. In terms of betraying the reader's expectations, the ending gets an A+, but it also voids the meaning of all the hard work in the rising action portion of the story, and reconfirms the reader's initial impression that Naoya is really just kind of a douchebag. It's sort of exasperating to see the characters take the eventual path that every reader would have chosen ages beforehand, but it's still quite in keeping with the story's theme of painfully flawed characters.

Cue was a follow up work from the following year after Sayuri's completion, and forgoes most of the heavy relationship themes for a story about acting and the theater. The story of a pair of middle school students who become involved in a tiny local theater troupe that gains notoriety when the lead actor is rumored to be a former rising film star who mysteriously cut his career short years before, Cue proves in the aftermath of Sayuri 1-go that Murakami is indeed an expert of pacing and story hooks. Cue also improves on Sayuri's frankly crude art. However, as I'm not particularly enthusiastic about theater acting, and given some developments and themes that I thought were stretching given the short length of the series, it didn't quite hook me as well as its predecessor. The best surprise is actually a four-chapter miniseries, "Junsui Age-Kojo," added to the end of the final volume, that combined the punchy pace and characterization of a one-shot with a pleasing extra length.

Takemitsu-zamurai 1-5 - Issei Eifuku & Taiyo Matsumoto

It's no secret that I am an unabashed fanboy of Taiyo Matsumoto, but even I was a bit nonplussed when Takemitsu-zamurai first appeared. His first major series after the conclusion of Number Five, Matsumoto joins forces with an old college friend, using Issei Eifuku's manuscript as the basis for this manga. Initially I pretty much slept on this manga -- despite the fact that I bought each volume as it came out, I largely forget the details of the story by the time the next one came around. But after finishing Vols 4-5 back-to-back, I feel confident in saying that once again, Matsumoto's doing one of the best things running in manga today.

Eifuku's story borrows a common theme of many contemporary tales of the samurai era: the deadly killer, harrowed by the slaughter he has committed and the incredible power of his blade, hides in a peaceful town and attempts to live a quiet life far removed from violence. If, like me, you immediately think, "That sounds like Rurouni Kenshin," you'd be correct, but the similarities stop right there. Unlike Nobuhiro Watsuki's cartoonish saga of videogame battles and shonen tropes, Issei Eifuku's tale is literary, poetic, and wrung through the pen of the most powerful artist in Japan. When last we had seen Matsumoto, he'd reached the apex of his "realistic period" encompassing Ping Pong and Number Five, when the crude but vivid chaos of Hanaotoko and Tekkon Kinkreet had given way to sharper detail and greater kinesis. When Number Five had concluded, you might have wondered how he could top the sheer weight of that work, and his answer was simple: don't attempt to top it, just reinvent and do something else.

Takemitsu-zamurai presents a sharp shift away from the realistic detail to a more stylized look, but rather than return to the European style of his early work, he has added a strong influence of ukiyo-e art, in fitting with the setting of the story. While some scenes may be unmistakable "Matsumoto-esque" work, others have a fanciful storybook quality. Rather than skewing his perspectives, he flattens them. Rather than filling in backgrounds with pre-printed tones, he uses ink brushes that give them an irregular watercolor styling. And as always, he has a master's touch when it comes to timing, deftly switching between different levels of detail as the scene calls for it. Even now, over twenty years into his career, long past the point when even the most individualistic of artists have honed and programmed their styles to be efficient to mass-produce, no one can surprise with the joy of new and unfamiliar looks with each turn of the page in the way that Taiyo Matsumoto does.

Another new characteristic found in the manga is its placid pacing. Matsumoto is no stranger to the practice of inserting "beat" chapters before the story continues. Just about every one of his series has a chapter without dialogue consisting of simple background scenes, the sight and sound of his universe breathing. But with his brief stories and tight plotting, it's virtually impossible for anyone to claim these are simple delaying tactics or padding out his volume total. Matsumoto's auteur's mentality have left him at odds with the usual manga rat race: "do whatever it takes to prolong popularity so you can get those regular paychecks." However, with Eifuku controlling the reins on the story of Takemitsu-zamurai, we see more detours and meanderings than if Matsumoto were penning the entire series himself. The volume count sits at five, with at least one or two to go yet, and an easy possibility of several more. It's hard to claim whether this is a good or bad thing -- virtually all manga artists are formulaic enough that after a certain point, you're no longer buying/reading to be surprised, but just to run out the rest of the plot. Kaiji Kawaguchi series are so predictable on the artistic side that you're not really reading a manga so much as a hideously fat and expensive Tom Clancy novel. But Taiyo Matsumoto is one of the few artists around that consistently deflects this issue, and I'd be crazy if I tried to explain the joys of reading and absorbing Takemitsu-zamurai only to follow that up by saying that I want it to end in the near future.

I realize that I'm probably doing Issei Eifuku a disservice with all the talk about Taiyo Matsumoto, but as he's sort of an unknown quotient, it's difficult to gauge how much credit to give each person in this artistic collaboration. Suffice it to say that the combination of story, dialogue and art contained in these pages and stemming from the talents of these two men is a sublime achievement and worth the attention of any enthusiastic follower of comic art.