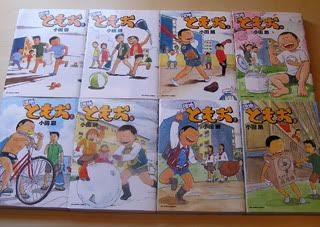

Danchi Tomoo (団地ともお)

by Tobira Oda (小田扉)

Published in Big Comic Spirits (Shogakukan)

8 volumes at present (2003-)

Amazon.jp

A charming and curious series from one of the more unique comedic artists in Japan, Danchi Tomoo is a story for adults about the trivialities of being a suburban Japanese child. A "danchi" is a high rise apartment complex that often contains multiple buildings (if you've ever read Otomo's Domu, you've seen one). Our protagonist Tomoo lives in a danchi, and thus, this is the story of his escapades with the eccentric cast of kids and characters that live there.

Tomoo (pronounced To-moh, not To-muu, though this is the punchline of a joke that is used once within the manga) is a classic lamewad kid in the vein of Doraemon's Nobita: Clumsy, stupid, lazy, obnoxious, impatient, yet somehow lovable. He's the ideal representation of a fond childhood for the legions of ne'er-do-well slacker 20somethings reading this manga. Tomoo and his classmates and friends are constantly involved in some kids' activity: playing sports (and losing), collecting things, catching bugs, and, as with all kids, getting tired of them. It's a boring set-up, but the trick to enjoying it is to recognize Oda's comedic formula. The special weapon of his arsenal is the shortened length of his chapters, on average 12 pages, rather than the typical 18. By working with less material, Oda is largely free from having to fully develop or stretch out a premise, making them punchy and loose. In fact, his forte is a sort of abrupt anti-conclusion, in which a chapter will end with no punchline or period at all. There is also a bittersweet edge to the mix that works well with the humor, and generally the two sides balance out, neither becoming too slapstick nor too serious. It took me a few volumes to really latch onto Oda's sense of humor and unique build-up and payoff methods, but once I did the flavor of the series really blossomed.

As with the majority of successful episodic comedies, Danchi Tomoo maintains an ever-burgeoning cast of eccentric characters, from Tomoo's classmates and family to the local residents of the danchi. The eccentricity is perfectly pitched to match the general feel of the manga; it's just odd enough to carry a sheen of artifice without being completely unbelievable, as in some of Oda's short material. Danchi Tomoo is a much more balanced and palatable mix than his maddeningly brilliant but inconsistent short story collections, but bits of that distilled nature shine through in the short "Captain Sports" excerpts, a manga that Tomoo and friends read about a mustachioed cyborg in a karate robe with a gyoza for an ear. Oda expertly fleshes out his side characters and reuses them, building details and staying consistent with them. Small arcs exist here and there: Tomoo visits his dad, who lives apart from the family on work assignment, an old man dies and his identical brother moves in, Tomoo befriends a baseball player. Tomoo gets a new jacket, and he is seen wearing it constantly several volumes from that point onward until it gets ratty. For an attentive reader, there is a wealth of such small surprises.

For me, Danchi Tomoo also carries another meaning. I've read my share of great series from Big Comic Spirits in the past, but when I visualize it in my head, I have a tendency to focus on the man-boy oriented schlock that chokes it, as in any weekly seinen magazine. But little gems like Danchi Tomoo always remind me that BCS is always good for at least 2-3 brilliant serials at any one time.