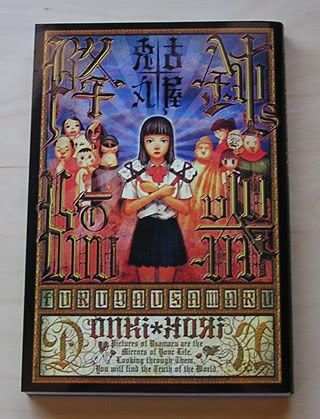

Today's entry was sparked by the arrival of a new package of books, some of which I am quite excited about. I've been on a big Kazuo Umezu kick as of late. No doubt some of you will be familiar with his most famous creation, the post-apocalyptic tale of horror and madness, Drifting Classroom, currently in English courtesy of Viz. I've never read more than a book or two of it, but as part of their ongoing "Umezz Perfection" line, Shogakukan has started publishing a new, deluxe edition, the first of which arrived in my hands today. Compared to the hysterically ugly covers of all previous editions, this new one, with a solid red scheme including red gilding on the pages and a neat picture superimposed on said gilding, is unspeakably tasteful. At 700+ pages, it's a massive tome, and is arranged like the entire series is really one giant book; the table of contents has a listing for three total books (the other two forthcoming as of this writing), with the page numbers being cumulative over the series. It even, bizarrely enough, ends abruptly in the middle of a chapter, with the remainder apparently kicking off the next book. One gets the impression that were it not logistically impossible to print all 2,300 pages in one book, they would have done it that way. It's really an attractive package, and well worth the $20 cost.

Additionally, I've been reading a small, bunko edition of Umezu's My Name Is Shingo, which I am belatedly realizing might be in line for the same deluxe treatment as Drifting Classroom, if this Umezz Perfection line ends up being a career-spanning effort. It's the story of a young boy and girl who program an assembly robot and manage to help it achieve sentience. Given that it was written in the early '80s, the nuts and bolts of the story mechanic are kind of laughable, but that would be missing the point, because with Umezu, it's never about the how or why, but simply drinking in the otherworldly atmosphere and profoundly weird dimension that his work inhabits. As a perusal of Shaenon Garrity's Drifting Classroom write-up will reveal, Umezu has all the subtlety of a sledgehammer, but its effects are undeniably unique and instantly recognizable.

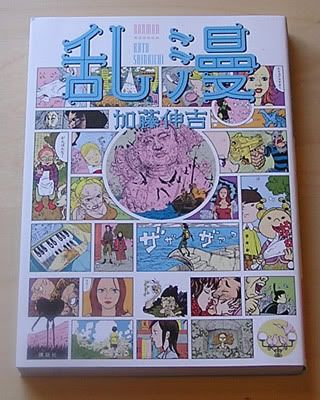

Other new acquisitions of particular interest (which I have not torn into yet) include Yoshiharu Tsuge's immortal classic, Neji-shiki (Screw Style), the Japanese edition of Akira, which I've only ever read in English, Shin Takahashi's latest book, Tom Sawyer, which is only marginally related to Twain's original, and a book titled Mankasu from the obnoxious idiot-child of the manga world, Gataro Man, best known(?) stateside for drawing the original manga that inspired the film Battlefield Baseball. Not being totally versed in his career works, I'm not sure if this manga is particularly special among his bibliography, but I should note that the title of this one, part of his tradition of incorporating his pen-name in the titles of all his books, is translated to the delightful handle, "Pussy Smegma."

Other, just slightly older releases which I have enjoyed immensely are the dual releases of the first two volumes of the Ikki series Children of the Sea and Dien Bien Phu. The former is the current series by naturalistic soul and all-around genius Daisuke Igarashi, well known for his titles Witches and Hanashippanashi. It's his first long-term epic, and though the first two (rather hefty) volumes cover a good amount of story, there's clearly quite a lot to go. This could be his shot at a legitimate hit, and I can't imagine that it will escape some kind of media adaptation in the future. The former title is a quirky take on the Vietnam War by illustrator/designer/manga-ka Daisuke Nishijima. As the link above will demonstrate, he has a very recognizable, cute and simplistic art-style which seems at odds with the rather bloody nature of his story, although I think the cognitive dissonance it creates is rather interesting. In addition to the uniquely "manga" take on the subject, with its caricatured characters and fantastical combat, Nishijima packs a lot of notes and background information about the culture and history of Vietnam at the end of the books, so despite being very quick reads, there is a lot to take in, overall.

Until next time!