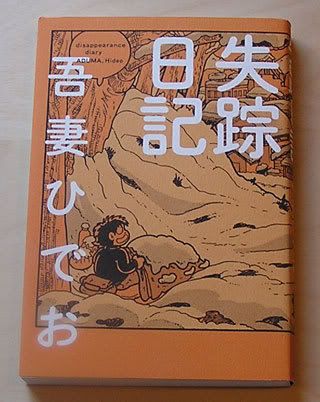

Disappearance Diary (失踪日記)

by Hideo Azuma (吾妻ひでお)

published in various places (East Press)

1 volume (2005)

Amazon.jp

Hideo Azuma's award-winning, non-fiction, soon-to-be-English work. For those who haven't yet heard the premise, Azuma was a moderately successful manga artist in the 1970s and '80s who fell into alcoholism and escaped his work by running away from his responsibilities in 1989 and going homeless. After this experience and his eventual return to normal life, he repeated the cycle in 1992, this time finding work in a new town as a gas pipe layer. In 1997, his alcoholism was so bad that he was forced into a rehab clinic. These three experiences form the three different chapters of the book, which also includes a few descriptions of his career in general scattered throughout.

The most immediately striking feature of the book is the dichotomy between the serious, depressing content and the buouyancy of the cheerful cartoon art. Azuma claims that he removed all realism from the art because it would be "tiring and depressing" to depict it that way, but without any experience with Azuma's previous work, I can't say whether this means that he could have drawn with more detail, or if this is his only style. Certainly the images of characters from his older manga appear to be in the exact same style as the people in Disappearance Diary. His previous work appears to be a mixture of frivolous, tittilating romantic comedies and light sci-fi, a B-level output enough to give him a cultish weirdo following -- I have a feeling Yuzo Takada owes no small debt to his formula.

As for Disappearance Diary, it lives up to its moniker, consisting largely of minor anecdotes of daily happenings. The first account, of his stretch of solitary homelessness, is easily the most brutal. Azuma describes his daily struggle with starvation and the cold in heartbreaking detail: eating grass, drinking discarded bottles of tempura sauce, ransacking garbage cans. The pipelayer and rehab sections are similar in execution, except that Azuma's personal quirks take a backseat to the eccentricities of his fellow workers and patients. Throughout, Azuma continues his goofy slapstick framing, leeching the realism and pathos of his experiences out of the manga. His insistence on distancing himself from the reality of the situation in his depiction because it would be "too depressing" is somewhat disingenuous, however. At face value, as the slightly silly and undramatic life of a homeless man, Disappearance Diary is boring. What makes it interesting -- and I believe that Azuma recognizes this -- is the distance between his version of events and what we can imagine to be the reality of the situation, all of the things he's left out. What was most shocking to me was the offhand revelation, after we have seen Azuma trotting out the lowest periods of his life, that he had a wife during these entire travails! You'd never imagine he was a married man if he hadn't admitted to it, and their relationship, other than the fact that she does his assistant work when he draws, is left completely in the dark. This facet of his life I found to be much more interesting than what he actually does tell us.

It's possible that my mild dislike of Disappearance Diary as it stands stems from the art, which I will admit is not to my liking. As well, the many accolades and awards possibly had me expecting something different, and those expectations clashed with my lukewarm reception. It's certainly an intriguing book, and its concept is a rarity in the world of manga. But fittingly enough, these traits I only find myself admiring from a detached standpoint, much like Azuma's book, and the true core of enthusiasm I could have felt toward Disappearance Diary is as hidden as the real events obscured behind his creative veil.

5 comments:

Soon to be English? Do tell...

D

Ahh, Aduma.... Yeah the guy was once more than an average mangaka. He was a winner of the Japanese Hugo Award for Best Sci-Fi manga in the late 70's (an honor he shares with Okano Reiko, Takemiya Keiko, Takahashi Rumiko, Hagio Moto and Otomo Kazuhiro (to name a few). He was one of the first artists to heavily mix gag style comedy into his sci-fi as he was influenced by the american New Hollywood movement of the 60's and early 70's.

Aduma is really known for being the father of Lolicon manga. His doujinshi work in the 80's created a lolicon boom and they also developed the biographical manga sector since he was long drawing his journals in manga format. His character designs have never been very detailed. Some of the women you see in the hospital and such are about as fancy as he gets. That style had long made him big with advertising fims and designers which is where he got most of his work around the time DisDiary was published. His designs influenced Takahashi and a number of animation studios.

Aduma is a pretty shy man. I met him in person at Comiket last year. Doesn't take well to fame or pressure. He was just drawing postcards to sell at the event before I wanted to shake his hand and buy his latest Diary. He didn't go to the last comiket but there were his assistants. His work has been piling up and in his latest diary (which you can order directly from him online) he describes his continued stuggles with his vices. When the pressure gets to him he becomes sick and self-destructive. Looks like he has a support team now that watches out for him though.

I found this Diary to be incomplete. Almost wish East Press could have waited and added the Kadokawa Shoten suppliment to have it make more sense. Given that a number of his titles have recently seen reprints getting to see the Aduma from his doujin diaries might reveal how this artist works and why he draws what he draws.

Oh and D, FanFare is going to release this in English later this year.

Thanks for the background info, Ed. I had wondered if part of the critical attention and award mania surrounding the book was not a case of the industry looking fondly on an old hand who came around again and actually produced something culturally/literarily significant.

It reminds me of Matt Thorn's comments of when he was on the panel for the Media Arts Manga Awards. He was pushing hard for one of the titles in contention, but the other judges, who were pretty stuffy old men, were locked in on Pluto, which only had maybe 1 or 2 volumes out at the time. Guess the call of Tezuka and Urasawa together was too much to resist...

Its possible that the industry was throwing him a bone. But I will say he has made his mark on the business. Lolicon and sci-fi wouldn't be the same without him. I know that comiket especially would not be the same. He practically made biographical doujin possible.

I just finished this book and I found anything but boring. I found the art interesting and definitely great contrast with the nature of the story.

Is it out in English yet? I actually read it in French from amazon.fr...

Post a Comment