Abara (アバラ)

by Tsutomu Nihei (弐瓶勉)

published in Ultra Jump (Shueisha)

2 volumes (2005-2006)

Amazon.jp

In the world of science fiction Japanese entertainment, there are naturally multiple spectrums of creation -- some childish (sentai), some hokey ("kaiju" monster movies), some conceptual and elegant (Leiji Matsumoto's Leijiverse). As well, we find a large variety of flavors in fandom. If detail- and factoid-heavy epics like the Gundam universe and Five Star Stories spawn walking encyclopedias like Trekkies or Star Wars fans, then Tsutomu Nihei's cultish fanbase is surely drawn in by the elements of Ridley Scott's original Alien film. Nihei uses his architectural background as a sweeping canvas upon which he sprawls those things which stood Alien apart from its forebears -- claustrophobic dread, desolate loneliness, futuristic decay, an absence of camp and H.R. Giger's sensual, inhuman designs. The result is one of the most striking and recognizable visual styles in manga. Though his 10-volume debut Blame! will no doubt always be his signature series, Abara is actually his most consistently high-quality work, and the best place to begin.

In contrast to Blame's lengthy, segmented and often baffling narrative, Abara keeps itself concise and potent with a simple, but no less vibrant conflict. In a future city hugging the base of massive, looming structures called "sepulchers," a mutated monstrosity known as a "white gauna" (gauna coming from an archaic Japanese term for a hermit crab) goes on a spree of destruction, moving faster than the human eye can see. Only Denji Kudo, a former member of a shady organization who has been given experimental "black gauna" capabilities, can stop it. There are various other characters and details to engage the thinking types, but the main attraction of Abara is this conflict between "good" black and "evil" white.

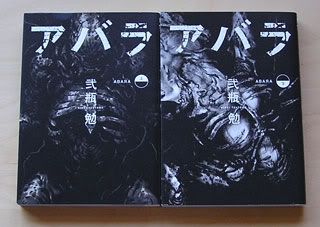

This duality is played to the hilt with the book design as seen above -- grimy and monochrome, the traditional two-volume "up-down" standard of Japanese literature is blended in with the black-white motif in the circles beneath the title. This logo is seen on the backs of the books as well, next to the English words "Black/White." Unlike the swirling yin-yang harmony of Taiyo Matsumoto's black and white that I wrote of last month, these are pure semicircles, rigidly absolute in their opposition, and never the twain shall meet. Abara's conflict plays out much the same, two sides of power locked in a breathtaking struggle. Perhaps Nihei's absolutist perspective is related to his love for American comics (see his Marvel-published Wolverine: Snikt), or perhaps that's reading too far into it. But it would be interesting to note that his breathtaking action scenes bear the highest similarities to another piece of Western entertainment, but one that borrows heavily from Eastern sources: The Matrix. Abara's detailed, kinetic battles pay much lip service to the iconic, exaggerated choreography of the Matrix, and Nihei's cyberpunk styling, though predating the Matrix's filming, fits it to a T.

So the action sequences are candy for the eyes and certainly the most instantly-noticable feature of Abara, but what truly sets it apart from Nihei's earlier work is the excellent balance of his various strengths. The silent introspection of Blame's splendid, numerous long-range shots is used sparingly to temper the frenetic action. The story is woven deftly and purposefully, in a manner that is more cinematic than serial. And though his protagonist Kudo is, like Blame's Killy, a weary and taciturn warrior of fate compelled to his task by great necessity -- and Nihei's characterization is, as always, bloodlessly unsentimental -- the designs of the characters are more detailed and consistent than ever before.

Of course, being approachable for Nihei doesn't mean it's a total walk in the park. I find his work similar in execution to the great American science fiction writer Gene Wolfe (Book of the New Sun) in their shared love for totally insular worlds that run by their own logic and demand the reader acclimate himself, rather than accomodate and thus compromise. Both authors define their worlds by certain conceptual rules, setting strict boundaries on their characters and their own narration to avoiding breaking the fourth wall and describing their fictional conceits in terms familiar to You, the Reader (circa 2007 AD). It's a philosophy that enriches its material and greatly increases the amount of rigorous thinking and imagination required, but carelessly applied, will lead to frustrating inscrutability -- a charge often leveled at Blame. However, Abara's hurdles are easily the lowest of Tsutomu Nihei's output, and with its high quality and short length, it makes the perfect introductory point for new readers.

6 comments:

Woo.

You're reviewing something I've acutally got.

I feel 62% more hip.

Nice review.

P.S. I sent you an e-mail about two weeks ago with the title "Could you please recommend me some easy manga?"(I was referring to easy to understand japanese), have you received it?

Hi ark, sorry about my utter slackness. I usually procrastinate or totally blow off questions like that because I never really know what would be considered "easy" to a beginning student. All I can tell you is that I started off reading a lot of Weekly Shonen Jump series. Detective Conan was another good one, just because it had so much information and text packed into it.

flyingrobots: no problem, thanks for replying!

I just found your blog recently, and I hooked! Perspicacious insights from a manga insider, what could be better? I just pray that any of the manga you cover are released in the states... especially this one by Tsutomu Nihei.

Keep up the good work!

Do you know where I can get Abara? Preferably online. I'm finding it difficult to find. Thanks!

Tas.

Post a Comment