Since I'm just banging this out before bedtime and with the momentum of a beer or two behind me, I'll run through these real quick in the order I see them on my shelf:

Goodnight Punpun 1-2 (Inio Asano)

Despite Asano's insistence that he was starting this with a fresh outlook, it's really quite familiar territory for him. The cartoony, iconic protagonist is sometimes comical and sometimes endearing, but otherwise isn't so different from his past outings, just starting from an earlier age. It's a charming and surprisingly affecting work that covers commonly-tread ground, but with Asano's patented sense of style and polish. The crusty record store clerk types among us will scoff and say that he's losing his edge and they've got a point, but for now I'm still cruising the wave.

Mysterious Girlfriend X 1-2 (Riichi Ueshiba)

These books actually arrived to me courtesy of a generous stranger (who I'm sure will see this at some point). I don't own anything else by Ueshiba but I'm vaguely familiar with his other material. We discussed it for a bit as a follow-up of sorts and found agreement that it seems to be a rather calculated attempt to gain a hit for Ueshiba, who's usually a little too weird and fetishized for mainstream acceptance (as far as the Afternoon readership goes)...but it's a very savvy attempt, and it seems to be working. Of course, you could say the same thing about Punpun above, but the difference here being that I generally dig Asano's shtick, while Ueshiba's just creeps me out a bit too much. Call it the hipster vs. otaku dynamic.

Kyomusume 1 (Kon Kimura)

Another Afternoon title, this from the author of the totally ignored Kobe Zaiju. It's frankly nearly unadaptable for a Western audience, thanks to its overabundance of tiny, between-panel vertical narration columns and truly bizarre and unmatched sense of humor... Which is a shame, because in a perfect world, it would be adapted and mindblowing. Essentially it's about a "huge girl" who is in every way (size, attitude, sexual appetite) just a hairy-chested caveman, with a "loli boyfriend" who is in every way (demureness, innocence, speed to tears) a helpless damsel. There are plenty of other twisted characters but the only thing that really remains constant is the devastatingly sarcastic and wordplay-saturated commentary. It's very dense stuff but pure quality. Worth at least three times the money you pay for it.

Ode to Kirihito 1-4 (Osamu Tezuka)

I'll be the first to admit that for a guy who's more well-read than 99.99% of English-speaking manga readers, I'm woefully unfamiliar with Tezuka. For one, where do you start? Essentially I've only ever sampled two very polar opposites of his career: Parts of Tetsuwan Atom (Astro Boy), the pinnacle of his early, child-oriented commercial works, and Adolf, one of his very serious, dramatic stories at the very end of his life. As much as I enjoyed Adolf, Kirihito totally blows it out of the water with its furious visual experimentation and rich themes. A lot of the visual work on display here--bizarre paneling, bold imagery--is brilliant and surprisingly fresh for a series from the early 1970s. Unfortunately I have a feeling that it comes off as "fresh" because the commercial manga community didn't have the guts to fill the void Tezuka created behind him with this material. Great story, great comic.

Beshari Gurashi 4-5 (Masanori Morita)

Morita's comedian manga, which flopped in Jump and had to be suspended when he was unable to keep up the weekly pace, picked up again in Young Jump where Morita's status with a generation of dudes stoked on Rokudenashi Blues and Rookies would be more forgiving of a lax schedule. My own personal interest in this series picked up momentum with these volumes too, especially now that it has gone past "funny teenager wants to be a comedian" into "funny teenager struggles to be a comedian." It doesn't sound like much of a difference, but the addition of big-time pro comedians and the presence of the comedy industry in the story has suddenly made it far more fascinating and well-defined. I've told people multiple times that this is a very hard story to grok for those who aren't familiar with or interested in the Japanese brand of comedy (and it has to be said that the actual comedy routines in the manga aren't that funny, much like say, the music scenes in Beck aren't that rockin'), but it's developed into a rewarding little series for those who do.

Chinomi 1-2 (Ryuta Yoshinaga)

Those who know me personally can attest that somehow, despite my utter disregard for the entire world of vampire-related fiction, it certainly has its dashing, elegant fangs stuck in my helpless neck (kill me now). Well let it be known that there is one vampire story in the entire world that I can tolerate, and I have found it. Chinomi eschews the time-honored traditions of vampires as either a) gothic aristocrats who ravage beautiful women for the titillation of unsatisfied housewives and frumpy D&D chicks everywhere, or b) inhuman, bestial monsters that rip shit to pieces for the uproarious enjoyment of drunken/blazed nu-metal dudes, and instead finds a comfortable compromise in a brand new endeavor, c) greasy, dim-witted ex-grunge gen-x slacker vampires!

Chinomi is the manga equivalent of finding an awesome band's demo tape, and realizing that no one else will ever enjoy it the way you do, and nothing else the band will do in the future can top it. It's just got too much character to ever be successfully replicated by the author. Yoshinaga is clearly putting everything he can think of in this manga. His art isn't particularly good; it has its quirks which will be interesting to comix nerds but isn't nearly attractive enough to interest a widespread audience. Instead, he compensates by simply cramming every page and panel with an impossible amount of detail, often making it difficult, if not nearly impossible to decipher what is happening. There is a ton of text and a ton of text bubbles. Bizarre references abound and I know that some people reading this will appreciate that in a single chapter, I spotted mentions (through dialogue or art) of Steven Seagal, John Candy and Don fucking Vito (of Jackass)! There are some moment where you cannot help but feel the cosmic connection to another man's mind, and I've learned to stop doubting those moments.

Tuesday, April 1, 2008

Wednesday, November 21, 2007

Latest News from the Front

Well, I didn't do a very good job at keeping this thing current. My excuses are typical: I just didn't have the motivation to keep up the pace, it took a lot of time and mental energy, and so on. Since I've had time to purchase a few more books since the last update, and thus refresh my stock of things to talk about, I'd like to warm up with some short spiels about current titles of interest. One of the things that makes writing full reviews difficult for me is that I often have to wrack my brain to form extra opinions to tie together into a legitimate "piece," so maybe by working shorter I can simply type out the entirety of my opinion in one place without any extra mental work.

Today's entry was sparked by the arrival of a new package of books, some of which I am quite excited about. I've been on a big Kazuo Umezu kick as of late. No doubt some of you will be familiar with his most famous creation, the post-apocalyptic tale of horror and madness, Drifting Classroom, currently in English courtesy of Viz. I've never read more than a book or two of it, but as part of their ongoing "Umezz Perfection" line, Shogakukan has started publishing a new, deluxe edition, the first of which arrived in my hands today. Compared to the hysterically ugly covers of all previous editions, this new one, with a solid red scheme including red gilding on the pages and a neat picture superimposed on said gilding, is unspeakably tasteful. At 700+ pages, it's a massive tome, and is arranged like the entire series is really one giant book; the table of contents has a listing for three total books (the other two forthcoming as of this writing), with the page numbers being cumulative over the series. It even, bizarrely enough, ends abruptly in the middle of a chapter, with the remainder apparently kicking off the next book. One gets the impression that were it not logistically impossible to print all 2,300 pages in one book, they would have done it that way. It's really an attractive package, and well worth the $20 cost.

Additionally, I've been reading a small, bunko edition of Umezu's My Name Is Shingo, which I am belatedly realizing might be in line for the same deluxe treatment as Drifting Classroom, if this Umezz Perfection line ends up being a career-spanning effort. It's the story of a young boy and girl who program an assembly robot and manage to help it achieve sentience. Given that it was written in the early '80s, the nuts and bolts of the story mechanic are kind of laughable, but that would be missing the point, because with Umezu, it's never about the how or why, but simply drinking in the otherworldly atmosphere and profoundly weird dimension that his work inhabits. As a perusal of Shaenon Garrity's Drifting Classroom write-up will reveal, Umezu has all the subtlety of a sledgehammer, but its effects are undeniably unique and instantly recognizable.

Other new acquisitions of particular interest (which I have not torn into yet) include Yoshiharu Tsuge's immortal classic, Neji-shiki (Screw Style), the Japanese edition of Akira, which I've only ever read in English, Shin Takahashi's latest book, Tom Sawyer, which is only marginally related to Twain's original, and a book titled Mankasu from the obnoxious idiot-child of the manga world, Gataro Man, best known(?) stateside for drawing the original manga that inspired the film Battlefield Baseball. Not being totally versed in his career works, I'm not sure if this manga is particularly special among his bibliography, but I should note that the title of this one, part of his tradition of incorporating his pen-name in the titles of all his books, is translated to the delightful handle, "Pussy Smegma."

Other, just slightly older releases which I have enjoyed immensely are the dual releases of the first two volumes of the Ikki series Children of the Sea and Dien Bien Phu. The former is the current series by naturalistic soul and all-around genius Daisuke Igarashi, well known for his titles Witches and Hanashippanashi. It's his first long-term epic, and though the first two (rather hefty) volumes cover a good amount of story, there's clearly quite a lot to go. This could be his shot at a legitimate hit, and I can't imagine that it will escape some kind of media adaptation in the future. The former title is a quirky take on the Vietnam War by illustrator/designer/manga-ka Daisuke Nishijima. As the link above will demonstrate, he has a very recognizable, cute and simplistic art-style which seems at odds with the rather bloody nature of his story, although I think the cognitive dissonance it creates is rather interesting. In addition to the uniquely "manga" take on the subject, with its caricatured characters and fantastical combat, Nishijima packs a lot of notes and background information about the culture and history of Vietnam at the end of the books, so despite being very quick reads, there is a lot to take in, overall.

Until next time!

Today's entry was sparked by the arrival of a new package of books, some of which I am quite excited about. I've been on a big Kazuo Umezu kick as of late. No doubt some of you will be familiar with his most famous creation, the post-apocalyptic tale of horror and madness, Drifting Classroom, currently in English courtesy of Viz. I've never read more than a book or two of it, but as part of their ongoing "Umezz Perfection" line, Shogakukan has started publishing a new, deluxe edition, the first of which arrived in my hands today. Compared to the hysterically ugly covers of all previous editions, this new one, with a solid red scheme including red gilding on the pages and a neat picture superimposed on said gilding, is unspeakably tasteful. At 700+ pages, it's a massive tome, and is arranged like the entire series is really one giant book; the table of contents has a listing for three total books (the other two forthcoming as of this writing), with the page numbers being cumulative over the series. It even, bizarrely enough, ends abruptly in the middle of a chapter, with the remainder apparently kicking off the next book. One gets the impression that were it not logistically impossible to print all 2,300 pages in one book, they would have done it that way. It's really an attractive package, and well worth the $20 cost.

Additionally, I've been reading a small, bunko edition of Umezu's My Name Is Shingo, which I am belatedly realizing might be in line for the same deluxe treatment as Drifting Classroom, if this Umezz Perfection line ends up being a career-spanning effort. It's the story of a young boy and girl who program an assembly robot and manage to help it achieve sentience. Given that it was written in the early '80s, the nuts and bolts of the story mechanic are kind of laughable, but that would be missing the point, because with Umezu, it's never about the how or why, but simply drinking in the otherworldly atmosphere and profoundly weird dimension that his work inhabits. As a perusal of Shaenon Garrity's Drifting Classroom write-up will reveal, Umezu has all the subtlety of a sledgehammer, but its effects are undeniably unique and instantly recognizable.

Other new acquisitions of particular interest (which I have not torn into yet) include Yoshiharu Tsuge's immortal classic, Neji-shiki (Screw Style), the Japanese edition of Akira, which I've only ever read in English, Shin Takahashi's latest book, Tom Sawyer, which is only marginally related to Twain's original, and a book titled Mankasu from the obnoxious idiot-child of the manga world, Gataro Man, best known(?) stateside for drawing the original manga that inspired the film Battlefield Baseball. Not being totally versed in his career works, I'm not sure if this manga is particularly special among his bibliography, but I should note that the title of this one, part of his tradition of incorporating his pen-name in the titles of all his books, is translated to the delightful handle, "Pussy Smegma."

Other, just slightly older releases which I have enjoyed immensely are the dual releases of the first two volumes of the Ikki series Children of the Sea and Dien Bien Phu. The former is the current series by naturalistic soul and all-around genius Daisuke Igarashi, well known for his titles Witches and Hanashippanashi. It's his first long-term epic, and though the first two (rather hefty) volumes cover a good amount of story, there's clearly quite a lot to go. This could be his shot at a legitimate hit, and I can't imagine that it will escape some kind of media adaptation in the future. The former title is a quirky take on the Vietnam War by illustrator/designer/manga-ka Daisuke Nishijima. As the link above will demonstrate, he has a very recognizable, cute and simplistic art-style which seems at odds with the rather bloody nature of his story, although I think the cognitive dissonance it creates is rather interesting. In addition to the uniquely "manga" take on the subject, with its caricatured characters and fantastical combat, Nishijima packs a lot of notes and background information about the culture and history of Vietnam at the end of the books, so despite being very quick reads, there is a lot to take in, overall.

Until next time!

Wednesday, July 18, 2007

New Manga and News

Hi all! I just got back from a long vacation in Montana and I've got tons of work to catch up on in a very short time, so I'm afraid more reviews will have to wait for a bit, but they will be returning! In the meantime, I just received another shipment of manga calculated to arrive just as I got back home. In the picture below, you'll see that I've almost entirely filled out my Taiyo Matsumoto collection - new titles are Nihon no Kyodai (Brothers of Japan), Gogo Monster, Zero 1-2 and the second volume of Takemitsu Zamurai. The only books of his that I don't have now are his artbooks, 100 and 101. In the upper right corner you will see Michio Hisauchi's 1988 Garo serial Takuran (Brood Parasite), an intriguing, medieval story of "persecuted peoples."

In the middle row can be seen the first five books of the ongoing Maison Ikkoku reprint (Urusei Yatsura is also receiving this treatment, and Ranma 1/2 got it a few years back), I suppose to coincide with the new drama. Ikkoku was always a favorite of mine back in my English manga days, and certainly the only Rumiko Takahashi series I'd spend my money at this point, so it's nice to have a spiffy new set. Following are the 22nd volume of 20th Century Boys and the first half of 21st Century Boys, the concluding piece, with the second half to be published in late September. Next to that are the latest volumes of Sing Yesterday for Me and Wanitokagegisu, and a new One Piece supplemental book.

The bottom row is an assortment of new volumes, from left to right: Hatsuka-nezumi no Jikan (Hour of the Mice) 3, Boys on the Run 6, Danchi Tomoo 9, Homunculus 8, Eden 16, A Spirit of the Sun 15, and Dosei Mansion 2.

In other news, I will be a member of a panel at the San Diego Comic Con next week! It's called Lost in Translation (scroll down to 6:00-7:00) and will feature several other well-known figures in our tiny little professional industry. I'm very flattered that I get to sit among them and more than a little nervous, but if you're there, stop on by and say hello!

In the middle row can be seen the first five books of the ongoing Maison Ikkoku reprint (Urusei Yatsura is also receiving this treatment, and Ranma 1/2 got it a few years back), I suppose to coincide with the new drama. Ikkoku was always a favorite of mine back in my English manga days, and certainly the only Rumiko Takahashi series I'd spend my money at this point, so it's nice to have a spiffy new set. Following are the 22nd volume of 20th Century Boys and the first half of 21st Century Boys, the concluding piece, with the second half to be published in late September. Next to that are the latest volumes of Sing Yesterday for Me and Wanitokagegisu, and a new One Piece supplemental book.

The bottom row is an assortment of new volumes, from left to right: Hatsuka-nezumi no Jikan (Hour of the Mice) 3, Boys on the Run 6, Danchi Tomoo 9, Homunculus 8, Eden 16, A Spirit of the Sun 15, and Dosei Mansion 2.

In other news, I will be a member of a panel at the San Diego Comic Con next week! It's called Lost in Translation (scroll down to 6:00-7:00) and will feature several other well-known figures in our tiny little professional industry. I'm very flattered that I get to sit among them and more than a little nervous, but if you're there, stop on by and say hello!

Saturday, June 9, 2007

Donki Korin

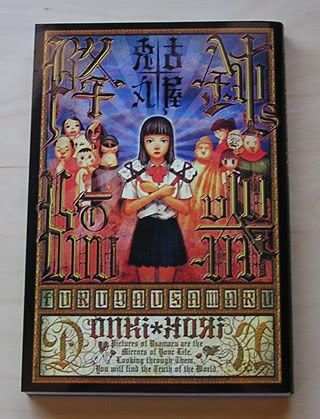

Donki Korin (鈍器降臨)

by Usamaru Furuya (古屋兎丸)

published in Da Vinci (Media Factory)

1 volume (1997-2004)

Amazon.jp

In an earlier post, I reviewed Usamaru Furuya's breakout masterpiece, Palepoli, and this review netted me a suggestion to check out its spiritual successor, Donki Korin (The Hammer Falls). Collecting six years' worth of the column he has run in the pages of serial novel and culture critique magazine Da Vinci since 1997, Donki Korin employs a unique structural format. On the right page of every spread is a short essay sent in by a reader and chosen by Furuya, and on the left page is a four-panel comic drawn by Furuya relating to the essay.

The book makes a good first impression with a gaudy, baroque cover that recalls Palepoli in both design and the variety of historical art styles employed. It also features hilariously bombastic blurbs in English on the front and back:

"Pictures of Usamaru are the Mirrors of Your Life."

"Looking through Them, You will find the Truth of the World."

"Readers wrote down Their Anger and Pleasure, then sent it to Usamaru."

"Usamaru received the Words of God, then drew a Hammer."

"Readers wrote the words of God, Usamaru drew a hammer of God."

"Usamaru and Readers shall bring down the Hammer together."

For the most part, the collaboration aspect is fruitful. The essays range from existential and poetic to absurd and comical, though typically more serious than not. Furuya's half of the collaboration is often simply a joke based on the subject or message of the essay. At the beginning he appears to be on a roll. In 1997 he was fresh off of Palepoli, which ran through 1996, and the art bears a strong similarity to the detail of that piece of work. His ideas, too, are fresh and smart, if not as surreal and boundary-destroying as what he exhibited in Palepoli. Perhaps he was attempting not to upstage the essay section (thus unbalancing the work), or perhaps he just wasn't interested in making the same kind of statements he had done previously.

However, over the course of the book (arranged chronologically) Furuya's half of the formula begins to suffer, his artwork growing simpler and more streamlined with time. There are a few throwbacks to his Palepoli days in the latter half of the book, both art-wise and with the use of recurring characters -- a feature he employed often in Donki's predecessor -- but for the most part there is a steady degradation of quality. In addition to the essay/manga content, there are a handful of short interviews sprinkled throughout, where Furuya called up some of the essay senders years later to discuss the subject and how things might have changed since then. While a nice touch, these interviews are mostly pointless and contain little added insight.

The best line of action to enjoying Donki Korin is to ignore my example and avoid comparing it to Palepoli. The book itself is an interesting concept, it is cleverly-executed and an entertaining read, regardless of its relation to the Usamaru Furuya's previous work.

Sunday, June 3, 2007

Flying Girl

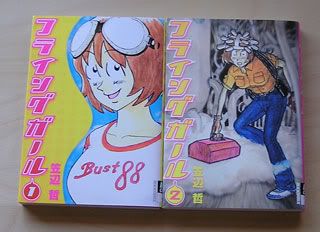

Flying Girl (フライングガール)

by Tetsu Kasabe (笠辺哲)

published in Ikki (Shogakukan)

2 volumes (2005-2006)

Amazon.jp

When Ikki was founded as a side publication of Big Comic Spirits in 2000, it was outfitted with a hefty lineup of critical and artistic favorites. With Taiyo Matsumoto (Ping Pong, Blue Spring), Naoki Yamamoto (Believers, Dance Till Tomorrow), Iou Kuroda (Nasu), Toyokazu Matsunaga (Bakune Young), Jiro Matsumoto, Kahori Onozuka and Yoko Nihonbashi, they attracted significant interest by loading up on big names. By necessity, as those artists finished their series -- one of the defining features of Ikki being its remarkable trust in its authors and total shunning of the popularity survey method of determining what to run -- some of them returned but others drifted off to other publications, and Ikki would be forced to develop its own new talent. Three artists in particular (Kazuo Hara [Noramimi], Hisae Iwaoka [Flower Cookies] and Tetsu Kasabe) have made Ikki their home for several books' worth of material, and with fairly similar styles combining a light fantastical touch with episodic content, represent what I consider to be the model of homegrown Ikki mangaka.

In Kasabe's case, he carved out his niche with a lengthy series of individual one-shots (six, in fact) over a span of 18 months, all of which were collected in the excellent Bunnies and Others, before starting on his first serial with Flying Girl. On paper, Flying Girl sounds like a cross between Urusei Yatsura's expand-and-conquer hijinx and Richie Rich's gadget-a-day utility. A completely boring, whitebread (or is that miso-and-rice?) government employee named Yamada is set to "Todd Duty" by his smirking boss -- Todd Duty being the supervision of eccentric genius inventor Professor Todd. Todd's inventions are superbly fascinating but often lacking in common sense or just plain dangerous, and it is these more questionable devices that Yamada is supposed to prevent the professor from creating in his mountainside retreat. Complicating matters is the beautiful and busty (her bust measurement in centimeters displayed on the very cover of the book) assistant Isogai, whom Yamada, being somewhat of a putz, immediately falls in love with. Ostensibly this infatuation and its potential realization are the ultimate goal of the story, but the clear star of the show are the inventions themselves.

Kasabe's creations exhibit the kind of dynamism necessary for this type of wacky, character-based comedy -- from the dopey yet stoic Yamada to the benevolent but aloof Professor, to the curious and rambunctious Isogai, as well as several others -- but it is the inventions themselves, many stemming from classic sci-fi archetypes, that act as the catalyst to bring about the humor. In one early chapter, Yamada attempts to slip Isogai the Professor's powerful new arousal drug, only to swallow it himself and share a passionate tryst with a goat, as the others look on and comment. In another, the Professor's "soul-switcher" exchanges the minds of Yamada and Isogai, then follows their mishaps in each other's bodies; Yamada finds that it's hard to run like a man when you have boobs and desperately avoids the temptation to feel himself up, while Isogai enacts her deep desire to pee off of a cliff. The gee-whiz inventions and their effects are nothing you couldn't imagine in the golden age of Tezuka and Leiji Matsumoto sci-fi manga, but Kasabe's addition to the formula is the giddy, anarchic lengths to which he pushes it.

In addition to multiple cases of the above-mentioned bestiality and sexual adventure, Flying Girl features a yakuza's severed, living head in a jar; his son, a "jungle boy" raised in the wild; a squat, bald mob boss who acts as the severed head's lover/caretaker and surrogate mother to the boy; as well as several talking animals - all the result of Professor Todd's inventions. Despite the level of chaos on parade, each installment generally ends with all wrongs righted, and the unruffled characters are willing to wryly comment on whatever disasters occur, such as one episode in which Yamada and the other characters are turned to stone for a year. When they are restored, he panics and calls his boss, expecting to be fired for a full year's absence, but the boss flippantly responds, "Oh, you're alive? Well, keep it up." This breezy nature is accentuated by Kasabe's rather plain, sketchy artwork, featuring simple, cartoonish portraits and humble, hand-drawn backgrounds, adding up to a light, quick read.

This formula of low-key cleverness is what distinguishes Kasabe and his compatriots Hara and Iwaoka from other artists and characterizes latter-day Ikki material. Flying Girl isn't exactly the kind of thing one would build a collection around, but it makes for excellent garnish.

Saturday, May 26, 2007

Chinatsu's Voice

Chinatsu's Voice (千夏のうた)

by Sho Kitagawa (きたがわ翔)

published in Young Jump (Shueisha)

3 volumes (2004)

Amazon.jp

I often think of Sho Kitagawa in very similar terms to another artist named Mochiru Hoshisato. Both spent most of their careers wedded to one publisher, Kitagawa to Shueisha's Young Jump and Hoshisato to Shogakukan's Big Comic and Big Comic Spirits. Both are responsible for one relatively well-known classic (Kitagawa's Hotman, Hoshisato's Living Game) in specific genres (family soap opera and romantic comedy, respectively). And the rest of their outputs are uniformly derivative and mediocre. It's as if each were playing a game of roulette, circulating through similar ideas until one stuck and achieved popularity. Once they had gotten the big hit, they never again hit upon that winning formula.

Lowered expectations might help with finding a worthy champion amid so much banality. Sho Kitagawa seems to specialize in painfully sappy family-based dramatic stories that are tailor-made to be adapted into TV drama format, so much so that it's almost astonishing that only Hotman has ever managed to win itself this treatment. Consider the concept: a young man acts as a surrogate father to his parentless younger siblings and takes care of his fragile little daughter at the same time. If that doesn't sound like an excuse to make housewives weep themselves silly on the couch, then I've missed the entire point of Japanese TV dramas.

Flash forward several years to Chinatsu's Voice, Kitagawa's (as of yet) last serial work. Having remembered enjoying Hotman in a passing way, I pick up the three books hoping for some light entertainment. The first thing that jumped out at me was the drastic improvement in the backgrounds, much like the huge shift between Slam Dunk and Vagabond for Takehiko Inoue. However, unlike Inoue, Kitagawa is not a great character artist, merely a solid one. So all of these vibrant and hyper-detailed natural backgrounds in Chinatsu's Voice can be chalked up to hiring some very expensive or diligent assistants. Kitagawa is like Shin Takahashi (Saikano) in being a male artist utilizing the more abstract paneling and flowery tones of shojo manga. The end result, especially in this case, is a quick-paced and breezy read that is crammed full of beautiful detail. While there's nothing wrong with those two things, their combination often feels empty when so much work is put into so little story, and Chinatsu's Voice, in keeping with Kitagawa's TV drama style, is anything but subtle. The reading experience is almost wasteful.

The titular Chinatsu is a 10-year-old girl who has moved to a rural beach town to live with her grandparents. Her magical singing voice can cause butterflies to dance around her, heal dying puppies, and mend the wounds in people's hearts. If just that description sounds sappy or trite, you can imagine the effect stretched over several books. She uses her songs to heal various problems and coat over various domestic situations in her own family and others. There's really not much to elaborate upon because that just about covers it.

If it seems like this review has been riddled with comparisons to other artists, it's not entirely because I'm simply grasping for straws. It's because Kitagawa himself doesn't really have enough of a personality on his own to merit discussing on his own terms. At the end of the day, Chinatsu's Voice is nothing more than yet another beautifully-drawn yet completely boring read.

Sunday, May 13, 2007

Abara

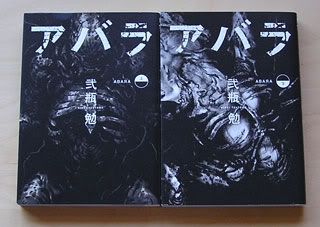

Abara (アバラ)

by Tsutomu Nihei (弐瓶勉)

published in Ultra Jump (Shueisha)

2 volumes (2005-2006)

Amazon.jp

In the world of science fiction Japanese entertainment, there are naturally multiple spectrums of creation -- some childish (sentai), some hokey ("kaiju" monster movies), some conceptual and elegant (Leiji Matsumoto's Leijiverse). As well, we find a large variety of flavors in fandom. If detail- and factoid-heavy epics like the Gundam universe and Five Star Stories spawn walking encyclopedias like Trekkies or Star Wars fans, then Tsutomu Nihei's cultish fanbase is surely drawn in by the elements of Ridley Scott's original Alien film. Nihei uses his architectural background as a sweeping canvas upon which he sprawls those things which stood Alien apart from its forebears -- claustrophobic dread, desolate loneliness, futuristic decay, an absence of camp and H.R. Giger's sensual, inhuman designs. The result is one of the most striking and recognizable visual styles in manga. Though his 10-volume debut Blame! will no doubt always be his signature series, Abara is actually his most consistently high-quality work, and the best place to begin.

In contrast to Blame's lengthy, segmented and often baffling narrative, Abara keeps itself concise and potent with a simple, but no less vibrant conflict. In a future city hugging the base of massive, looming structures called "sepulchers," a mutated monstrosity known as a "white gauna" (gauna coming from an archaic Japanese term for a hermit crab) goes on a spree of destruction, moving faster than the human eye can see. Only Denji Kudo, a former member of a shady organization who has been given experimental "black gauna" capabilities, can stop it. There are various other characters and details to engage the thinking types, but the main attraction of Abara is this conflict between "good" black and "evil" white.

This duality is played to the hilt with the book design as seen above -- grimy and monochrome, the traditional two-volume "up-down" standard of Japanese literature is blended in with the black-white motif in the circles beneath the title. This logo is seen on the backs of the books as well, next to the English words "Black/White." Unlike the swirling yin-yang harmony of Taiyo Matsumoto's black and white that I wrote of last month, these are pure semicircles, rigidly absolute in their opposition, and never the twain shall meet. Abara's conflict plays out much the same, two sides of power locked in a breathtaking struggle. Perhaps Nihei's absolutist perspective is related to his love for American comics (see his Marvel-published Wolverine: Snikt), or perhaps that's reading too far into it. But it would be interesting to note that his breathtaking action scenes bear the highest similarities to another piece of Western entertainment, but one that borrows heavily from Eastern sources: The Matrix. Abara's detailed, kinetic battles pay much lip service to the iconic, exaggerated choreography of the Matrix, and Nihei's cyberpunk styling, though predating the Matrix's filming, fits it to a T.

So the action sequences are candy for the eyes and certainly the most instantly-noticable feature of Abara, but what truly sets it apart from Nihei's earlier work is the excellent balance of his various strengths. The silent introspection of Blame's splendid, numerous long-range shots is used sparingly to temper the frenetic action. The story is woven deftly and purposefully, in a manner that is more cinematic than serial. And though his protagonist Kudo is, like Blame's Killy, a weary and taciturn warrior of fate compelled to his task by great necessity -- and Nihei's characterization is, as always, bloodlessly unsentimental -- the designs of the characters are more detailed and consistent than ever before.

Of course, being approachable for Nihei doesn't mean it's a total walk in the park. I find his work similar in execution to the great American science fiction writer Gene Wolfe (Book of the New Sun) in their shared love for totally insular worlds that run by their own logic and demand the reader acclimate himself, rather than accomodate and thus compromise. Both authors define their worlds by certain conceptual rules, setting strict boundaries on their characters and their own narration to avoiding breaking the fourth wall and describing their fictional conceits in terms familiar to You, the Reader (circa 2007 AD). It's a philosophy that enriches its material and greatly increases the amount of rigorous thinking and imagination required, but carelessly applied, will lead to frustrating inscrutability -- a charge often leveled at Blame. However, Abara's hurdles are easily the lowest of Tsutomu Nihei's output, and with its high quality and short length, it makes the perfect introductory point for new readers.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)