I typically get books in two different ways. First, I tend to order my specialty books through Acclimate Solution. It's pretty simple; I email them a list of titles and ISBNs, and they tell me what they can get and quote me a price. I've been making orders of 20-30 books every 1-2 months for the past three years or so, and I'm pretty happy with the results. It's good for tracking down things you wouldn't necessarily find in a bookstore and if a book is out of print, they'll offer to buy it from auctions or Amazon Marketplace sellers, who typically don't ship out of Japan.

The other way I get books is from the local Sanseido bookstore in San Diego, which is located within Mitsuwa Supermarket. I tend to think of it as like an airport bookstore. It doesn't have great selection but you can always count on it to have the latest One Piece, or Mitsuru Adachi book... things I wouldn't need to spend shipping on.

It just so happens that I got two hefty packages from Acclimate today, so I thought I'd share what I got. Feel free to leave a comment if there's anything you'd want to see me review sooner rather than later, or if you just want to make fun of my taste in books.

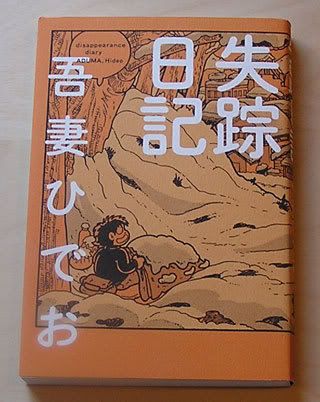

I typically get a mix of both recent releases of series I'm following, and a few complete series of an author or two whose library I'm trying to fill out. Today was a big Taiyo Matsumoto day. I've had all 8 volumes of Number Five for a while, and last order I got the recent one-volume omnibus edition of Tekkon Kinkreet (Black & White) that was released to tie in with the animated movie. This month I decided to splurge and picked up Blue Spring, Hanaotoko, and a very odd edition of Ping Pong. I highly approve of Shogakukan's habit of releasing Matsumoto's books in A5 formats and larger -- Hanaotoko and Blue Spring are both examples of this. My No. 5 and Tekkon books are B5, which is even larger, the size of the original magazines they were published in. Ping Pong has multiple editions in different sizes, so I went for broke and paid extra for the used out-of-print B5 edition that was released to coincide with the Ping Pong film. Oddly enough, though it's labeled as three volumes (A, B, C), each of these is just three very thin (100 pg.) books held together with an obi, making nine in total. I'm a bit disappointed in the flimsiness, but I can put up with it for the larger format. They also come with stickers!

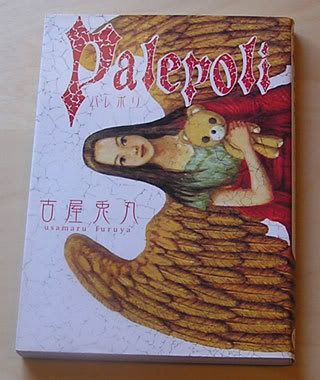

The second big storyline (ooh, I do like to dramaticize my shopping habits) was a trio of Kotobuki Shiriagari books: Jacaranda, A*su, and Hinshi no Essayist. The hype from his recent Angouleme award and some intriguing descriptions from Adam Stephanides' blog caught my interest, and I'm looking forward to tearing into these. I also acquired two more artsy-fartsy books: Kan Takahama's Awabi (I haven't read her yet) and Usamaru Furuya's Donki Korin, which was recommended to me as a good follow-up to Palepoli.

Moving on to more entertainment-minded fare, I purchased the entire output of my latest man-crush, Kengo Hanazawa. Hanazawa's two series for Big Comic Spirits, Ressentiment (4 volumes) and Boys on the Run (5, ongoing) have had me totally spellbound for the past month, as I'm sure anyone within earshot can confirm. While ostensibly categorized as romantic comedies (which usually means stay away), Hanazawa's savagely funny sense of humor and hefty doses of pathos make these books read like cousins to Minoru Furuya's recent work (Ciguatera, Wanitokagegisu).

I also paid out the wazoo for used versions of Rurou Seinen Shishio, an out-of-print two-volume series from Shinkichi Kato that I mentioned in the Ranman review (the price I pay for my beloved favorites)... As well as these new volumes in the following series:

A Spirit of the Sun v.14 (Kaiji Kawaguchi)

Dorohedoro v.9 (Q Hayashida) - a secret favorite of mine

Freesia v.8 (Jiro Matsumoto)

Shojo Fight v.2 (Yoko Nihonbashi)

Hyougemono v.4 (Yoshihiro Yamada)

Biomega v.1-2 (Tsutomu Nihei) - the new Shueisha edition

Vinland Saga v.4 (Makoto Yukimura)

(click for fullsize version)

Top (L-R): Ping Pong, Hanaotoko, Blue Spring, Dorohedoro

Middle: Jacaranda, Awabi, Donki Korin, Hinshi no Essayist, A*su, Rurou Seinen Shishio, Biomega, Shojo Fight

Bottom: Ressentiment, Boys on the Run, Hyougemono, Vinland Saga, Freesia, A Spirit of the Sun

Moving on to more entertainment-minded fare, I purchased the entire output of my latest man-crush, Kengo Hanazawa. Hanazawa's two series for Big Comic Spirits, Ressentiment (4 volumes) and Boys on the Run (5, ongoing) have had me totally spellbound for the past month, as I'm sure anyone within earshot can confirm. While ostensibly categorized as romantic comedies (which usually means stay away), Hanazawa's savagely funny sense of humor and hefty doses of pathos make these books read like cousins to Minoru Furuya's recent work (Ciguatera, Wanitokagegisu).

I also paid out the wazoo for used versions of Rurou Seinen Shishio, an out-of-print two-volume series from Shinkichi Kato that I mentioned in the Ranman review (the price I pay for my beloved favorites)... As well as these new volumes in the following series:

A Spirit of the Sun v.14 (Kaiji Kawaguchi)

Dorohedoro v.9 (Q Hayashida) - a secret favorite of mine

Freesia v.8 (Jiro Matsumoto)

Shojo Fight v.2 (Yoko Nihonbashi)

Hyougemono v.4 (Yoshihiro Yamada)

Biomega v.1-2 (Tsutomu Nihei) - the new Shueisha edition

Vinland Saga v.4 (Makoto Yukimura)

(click for fullsize version)

Top (L-R): Ping Pong, Hanaotoko, Blue Spring, Dorohedoro

Middle: Jacaranda, Awabi, Donki Korin, Hinshi no Essayist, A*su, Rurou Seinen Shishio, Biomega, Shojo Fight

Bottom: Ressentiment, Boys on the Run, Hyougemono, Vinland Saga, Freesia, A Spirit of the Sun